From left to right: Wayne Trevathan (CFA), Jan van Rooyen (SACC), Karl Preiss (FIFe), Steve Crow (GCCF), Eric Reijers (WCC President). Andreas Möbius (WCF) Vickie Fisher (TiCA). Front Row: Chris Lowe (NZCF), Cheryle U'Ren (CCCA), Penny Bydlinski (WCC Secretary) and Julian Schuller (ACF).

After seven years the Congress was back in the United Kingdom, In 2006 it was hosted in Hatfield by the FIFe member and at that meeting the GCCF was one of the three organisations applying for membership, now they were the hosts. It is interesting to note that the WCC membership has, in the interim, grown from six to nine members.

At the current meeting all nine organisations were represented: Australian Cat Federation (ACF) by its International Liaison Officer, Julian Schuller, Co-Ordinating Cat Council of Australia (CCCA) by its International Liaison Officer, Cheryle U’Ren who is also Vice-President of the WCC, Cat Fanciers Association (CFA) by Wayne Trevathan, Fédération Internationale Féline (FIFe) by its Vice-Treasurer Karl Preiss, and the WCC President Eric Reijers, Governing Council of the Cat Fancy (GCCF) by its Chairman, Helen Marriot-Power, New Zealand Cat Fancy (NZCF) by its Honorary Secretary, Chris Lowe, Southern African Cat Council (SACC) by Jan van Rooyen, The International Cat Association (TICA) by its President, Vickie Fisher and the World Cat Federation (WCF) by its President Anneliese Hackmann and by Andreas Möbius.

The hosts had arranged a tour of Cambridge on Friday and, despite the rather dreary weather, this was very enjoyable. Whilst walking beside the river in the area known as ‘the backs’ because of the many colleges which back on to it, a guide explained the grounding of the ancient University of Cambridge and, whilst pointing out various other interesting buildings, took the group around the magnificent chapel of Kings College, which is well-known for its annually broadcast Choral Evensong on Christmas Eve. After an excellent lunch at an Italian restaurant and a time for exploring the city, the group met again for choral Evensong at Kings College Chapel. As always, this was a beautiful and uplifting experience and we are grateful to our hosts for arranging it.

On Saturday all of the delegates were active as judges at the two shows being run back to back; the Suffolk & Norfolk Cat Club’s annual championship show and a special GCCF World Championship Show. These shows were well organized by the GCCF Chairman, Helen Marriott-Power and her team and ran smoothly in a relaxed and friendly atmosphere.

The day was rounded off by a Gala Dinner in which everybody took part.

On Sunday 19th the Seminar and Open Meeting took place in the Belfry Hotel, Cambourne near Cambridge, where the delegates were staying. The day was chaired by Dr Bruce Bennett who opened the event by introducing the WCC President, Mr Eric Reijers who, in turn introduced the delegates who each gave a brief presentation of how their organization promoted “Ethical and Responsible Cat Breeding”, which was the theme of the Seminar.

The presentations:

In his introduction Mr Reijers spoke of the partnership which existed between WCC and Royal Canin and explained how helpful this had been in enabling the WCC weekends to take place. He also mentioned the project of producing a new “Cat Encyclopaedia” which WCC was working on together with Royal Canin. He spoke of the role Royal Canin was playing in promoting the cat breeds, which he felt was very important to the fancy as, unlike dog breeds with which the average person is familiar, the different cat breeds were not known. He pointed out that the WCC was not an executive body, those powers remained with its members but its purpose was to promote harmony between the bodies. He thanked GCCF for arranging the weekend.

Professor Sir Patrick Bateson

After a coffee break the first Speaker of the day was Professor Sir Patrick Bateson, Emeritus Professor of Ethology at the University of Cambridge. Sir Patrick is also a cat lover and had been involved in the introduction and breeding of the Egyptian Mau in the United Kingdom. He spoke on the welfare aspect of breeding cats. He had heard the delegates presenting the measures taken by their own organisations and was impressed, particularly with the measures being taken in Australia. He also considered the GCCF’s recommendations to be excellent.

Pointing out that it is inappropriate to speak of ‘animal rights’ in the sense that ‘human rights’ are referred to, since human rights also involve responsibilities and that was not true for an animal. The concern that was felt by the animal lover was the desire to minimize suffering. He then spoke of experiments to identify stress and pain in animals. Stress, he said, could be measured physiologically. He related experiment with rats and with starlings, which illustrated their reaction to stress and its adverse effect on the health of the animal.

Identifying pain in animals could be difficult and he showed pictures of a dog with rheumatic pain both before and after analgesics had been administered; the difference in expression could clearly be seen.

Turning to in-breeding, Sir Patrick maintained that most pedigree cats were probably much more inbred than their owners knew as it was difficult to assess the co-efficients of in-breeding from a four or five generation pedigree. He spoke of the side effects of in-breeding, primarily that there was less likelihood of survival, a depressed reproduction system giving rise to lower birth rates and indifferent mothering as well as a reduction in the immune system making such animals more susceptible to disease. He pointed out that the conformation of a cat can be changed rather quickly, probably in about twenty years and suggested that the reason that the conformation of pedigree cats changed was probably because judges gave preference to an animal which was outstanding in certain ways and this resulted in breeders trying to produce the same look. He was not in favour of what he referred to as ‘novelty breeds’ founded on mutations, which he thought could not survive in the wild. Referring to the Scottish Fold, he pointed out that the ears were a major sensory organ of the cat and considered it wrong to interfere in their function.

Speaking of breeding for temperament, Sir Patrick stressed the need for handling kittens from a very early age. There was, he said, a small time frame in which attachment took place and if the kitten was not socialized in that period, it might never become a good pet.

He then spoke of epigenetics, which he explained showed that the condition of the mother affected the characteristics of the animal. A lot of work had been done on humans, particularly the human foetus with respect to the conditon of the mother and its effect on the offspring.

He further referred to Darwin’s “The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals” which contains a picture of a cat with its tail held high, rubbing its body against the legs of a chair. Holding a tail at this angle is peculiar to the domestic cat and is never seen in the wild cat population; it appears to signal a lack of aggression. He then spoke of cats in Egypt where they had been revered and evidently bred on a very wide scale and suggested that temperament would have played a large part in their selection.

Sir Patrick concluded by mentioning a book of behavioural studies “The Domestic Cat” which he had worked on together with Dennis Turner of the Institute for Interdisciplinary Research on the Human-Pet Relationship, Switzerland. A new edition of this book will appear later in the year and he recommended it for its interesting articles and information on this subject.

Laureline Malineau, Breeders Communication Manager for Royal Canin.

The next speaker was Laureline Malineau who is the Breeders Communication Manager for Royal Canin, with whom the World Cat Congress has a partnership. Ms Malineau spoke of the “passion for cats” which was shared by Royal Canin and the cat fancy in general. She stressed that the Royal Canin’s mission was to bring the best for the cat.

She related how Royal Canin had started when, in 1957, a veterinarian had become tired of seeing dogs with eczema in his clinic. He was convinced that this eczema was the result of the dog’s diet so he developed a diet that proved to be effective. That was the beginning of Royal Canin and it was the principle that held good in the present as they were always looking for means to improve the health of cats and dogs.

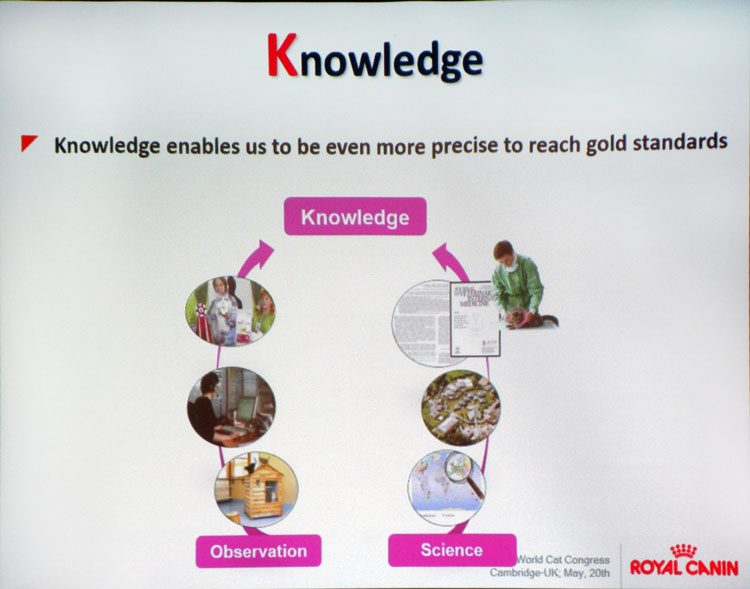

Knowledge was vital and Royal Canin also had partnerships with veterinarians, which enabled them to be more precise.

Observation was also important and they had studied the way cats ate in order to produce a kibble which was not only palatable but of the right size and shape for the cat to eat. Breeders’ observations were a constant source of information to them. Selection is as important to Royal Canin as it is to the breeder, whilst the breeder selected for healthy cats which were good representatives of their breed, Royal Canin selected for the best ingredients to put into the diet. In these ways she felt there was a common purpose and this was why they had a partnership with WCC; through this partnership they could share knowledge and promote the pedigree cat.

She spoke briefly of the project of a new “Cat Encyclopaedia” on which they were working with the WCC. She thought it was important for the public to know the characteristics, temperament and other information on the different breeds, which would be of assistance to prospective purchasers. She also showed a sample page of the projected book showing all the information that would be available, together with the standards of those organisations which were members of the WCC.

Professor Tim Gruffyd-Jones

Following the lunch break Professor Tim Gruffyd-Jones took as this title “Health of Pedigree Cats – Past, Present and Future”. Professor Gruffyd-Jones is a well known speaker to the WCC as well as being known personally to many of its delegates. Apart from being a senior veterinary specialist with the Feline Advisory Bureau (now known as International Cat Care), the fact that he has also been involved with breeding cats makes his views even more interesting to the cat breeder.

After expressing his appreciation of the theme of the Seminar, Professor Gruffyd-Jones asked how many people had been involved in rescue cats. He had, himself, quite a lot to do with rescue organisations and was aware that there was some intolerance towards pedigree cat breeders as those that worked in these organisations were aware that there were too many cats and not enough homes. He felt, however, that there was room for all cats.

Speaking of breeding, he commenced by looking at an optimal litter size. In cross-bred cats the average litter size was four. Singleton litters were rare. He referred to the Feline Advisory Bureau, which was equivalent to the Winn Foundation in the United States and consisted of various veterinarians and breeders who were interested in the welfare of cats who work alongside the cat fancy. The FAB had collected information on litter size in different breeds and found there was some variation. He commented on the fact that it had been said that in-breeding affected litter size and pointed out that this was not true in all breeds. Whilst some breeds habitually had litters of 3 or 4 and sometimes singletons, others regularly had larger litters. He related what he believed to be a record, which was a Burmese cat that had given birth to 17 kittens and had, with some help, managed to rear them all. There was a disparity between pedigree and non-pedigree cats and whilst stating that ‘mother nature’ usually gets things right, he questioned whether there was actually an optimal litter size.

A further study had been made on dystocia, being difficult births that could lead to caesarian sections. They had looked at this in terms of the head construction of the cat, mesocephalic breeds, that is those of average head shape such as the Abyssinian or the Korat had less frequency, the brachycephalic breeds being cats with flatter faces such as Persians, Exotics and to a lesser extent, British shorthairs had a higher percentage but the fact that they were breeds having larger heads, which were less likely to go through the birth canal easily, and also smaller litters, with proportionately large kittens, had to be taken into account. However, there was a striking difference in the frequency of dystocia between those head types. They had also looked at cats with extended heads such as Siamese and Orientals and found that they had an even higher proportion of dystocia. This could be explained by the larger litters in these breeds that could lead to uterine inertia, which can occur after a queen has had four or five kittens and is too tired to continue.

Another point to be borne in mind was that it was peculiar to the cat that kittens in the later stages of pregnancy produce hormones, which control the maintenance of pregnancy and also initiate parturition. These hormones set off the whole birthing process and in a litter of only one or two kittens, there may not be enough of these hormones produced to affect that process. This was another reason why small litters may lead to problems with dystocia.

Survival of kittens was linked to litter size and where there were large litters, there were a higher percentage of stillbirths.

Professor Gruffyd-Jones concluded that litter size did matter and in order for the breeder to select for this, it was advisable to choose a queen who herself came from an average size litter. The father also needed to be considered. The stud cat does not influence the litter size of the litters he sires but he will influence the ovulation rate of his daughters, so if he is from a large litter, his daughters are more likely to produce large litters.

Moving on to veterinary aspects, this was to be divided into three parts – the past, the present and the future.

He posed a rhetorical question “What do you think your veterinary surgeon thinks of you as a breeder?” Some veterinary surgeons had a fear of breeders whom they found intimidating. Most cat breeders were female and a recent survey had revealed that cat breeders had a higher educational attainment level than dog breeders. He found also that cat breeders were quite IT knowledgeable and spent time in keeping up to date on current cat health and welfare problems. It was not uncommon for a veterinary surgeon to come to a FAB lecture in order to keep one step ahead of the cat breeders! This, he felt was very positive. He had been impressed to hear from the various organisations how the cat fancy was putting heath and welfare at the top of their lists. He also referred to the “vetting-in” procedure that is common in some cat shows, which he thought contributed to ensuring the health of cats at shows.

Speaking of the past, he related his own experiences with his Abys, one of which proved to be positive for FeLV. At this time Feline Leukaemia was prevalent but because the breeders responded in a sensible manner by testing and selecting, as this was before the time of vaccination, the incidence of FeLV fell dramatically. He thought this was a good example of how breeders had handled things in the past.

Turning to the present, he thought schemes such as the GCCF accredited breeders scheme and similar schemes in other organisations, were to be applauded. In some organisations there was a system of mentoring where an experienced breeder would mentor a novice breeder. All of these things were very positive. Again within GCCF, the breed councils had been asked to come up with a document on good practice for their particular breed. He considered that a lot of useful things were currently being done in the interests of healthy breeding.

Looking at the future, the cat fancy needed to be aware of the fact that there was a real focus on health and welfare. In the UK a new Animal Welfare Act with a requirement for individuals to take responsibility for the animals they owned and to ensure that their requirements were met, had promoted awareness of this issue. Another issue which had brought the focus on health and welfare was those concerning dog breeding, There had been television programmes on dog breeding which led to reports from the British Kennel Club and an independent enquiry had been produced by Sir Patrick Bateson. This he thought could also focus attention on cat breeding and breeders could not be complacent about their position. He considered it essential that breeders ensured that their ‘house was in order’ as it was inevitable that it would be the subject of scrutiny in the future. Speaking of dogs, he said that the public had been, in his opinion rightly, outraged at the fact that some dog breeders had been in denial about breeding animals with neurological problems caused by a genetic condition which led to a dreadful quality of life and early euthanasia. Another example had been of breeds whose standard for gait promoted the development of hip dysplasia. This showed a direct conflict between the health and welfare of the animals and what the breeders were striving to produce.

Professor Gruffyd-Jones thought that the cat world was much better in respect of the health of its breeds. There were not the vast differences in phenotype in cats as were seen in dogs, he cited for example the huge difference between a Chihuahua and a Great Dane. If selective breeding is being used, genetic problems become more likely but these were not restricted to pedigree breeds. He cited a problem that was seen in non-pedigree cats but added that it was almost never seen in pedigree cats, so it cannot be said that hereditary conditions were exclusive to pure-bred cats.

He then mentioned measures being taken currently and cited GCCF’s General Breeding Policy which he considered to be an excellent document and listed some of the most well known genetic tests which were currently available and which were effective to enable breeders to eliminate certain diseases from their cats. He cited the test for PKD which had been developed by Professor Lyons at UC Davis. Since this test was first used in 2005 when the incidence of PKD was about 30%, it had now dropped to under 5%. He considered that breeders had welcomed and used the test, which was something for which they could be proud.

He showed a photograph of a Burmese suffering from Hypokalaemia which was a condition seen not only in this breed. It is a hereditary condition associated with a low level of potassium in the blood. It produces muscle weakness that can affect the cat holding its head up properly and in some instances also in walking around. Professor Lyons had researched this and there was now a diagnostic test available. This was a good example of where breeders had identified a problem and had approached Professor Lyons’ laboratory for help in sorting it out.

The next question would inevitably be as to how these gene tests would be implemented. More tests would become available as time went on. One possibility was that all cats were screened and no cats with genetic problems would be used in breeding. The disadvantage of that method would be to reduce the gene pool. Most genetic faults were due to a recessive gene and when a case arose it meant that both parents were carriers. However, with a gene test it would be possible to use carrier cats so long as they were not mated to another carrier. Subsequent testing of the progeny would identify which were carriers and thus it would be possible to continue breeding. The next question was how this was to be regulated. Were there advantages in having an independent body record the results? The other way was to rely on the honesty of breeders. Nowadays bucal swabs were used and the majority of samples which were sent came from breeders themselves. Alternatively, vets could be used to collect the swab and they would be able to read the microchip on the cat at the same time, however there would be charges involved. It had also been suggested that these records should be maintained by registering bodies, which had been done in the case of Gangliosidosis in Korat cats in the GCCF,

Some tests were quite complicated. He cited HCM, which is seen particularly in the Maine Coon and the Ragdoll and where tests were now available. However, the correlation between the test results and the development of the disease is not predictable. It was therefore necessary to learn how to use these tests.

Finally, he spoke of criticism, saying that it could be more meaningful if it came from a friend, and maintaining that he was a friend, both as a veterinarian, a cat lover and a breeder. He referred to another interest of his, which was sheep and said that there was a saying amongst sheep people that the biggest risk to a sheep was another sheep, meaning that where a number were kept indoors together the spread of disease was greater. This, he thought, was also true of cats, as the spread of infectious diseases was dependent upon the number of cats which were being kept in one place. Respiratory virus infections were very difficult to control, despite vaccinations, and these were particularly prevalent where cats were kept in large groups. Tests had been taken on healthy cats and it was found that about a quarter of pedigree cats were carrying caliche virus whilst being perfectly healthy themselves. Two surveys had been done, one before the vaccines had been available and another when they had been around for some time. It was clear that vaccination made no difference at all to the prevalence of the caliche virus at. The other big problem was FIP and the more cats being kept together in one place, the more likelihood there was of FIP developing. It was generally said that if numbers increased beyond about six or seven in a group, the chances of having FIP escalated dramatically. Another aspect was that not all cats like to live in a group and behavioural problems could develop if the group was a large one. He thought this was an important issue which cat breeders should address because of its implications both on health and behavioural problems. He understood how easy it was to end up with more cats than were originally intended and he thought breeders could try and help if they knew of others in this state.

The other issue was extremes of conformation, although a big issue in the dog world, it was less so in the cat world. Most criticism had been aimed at facial conformation and he did think it was possible that in the search for excellence breeders looked for something more than the average good quality and the pursuit of this aim could lead to extremes. These extremes could lead to health problems. All cat specialists would agree that the main concern in the breeding of pedigree cats was the numbers being kept in one household and the extremes of conformation. Professor Gruffyd-Jones thought these facts should not be ignored. He pointed out that if the Press were to focus on the cat fancy, they would only look at the extremes which led to problems, they would not look at the good things, such as elimination of Gangliosidosis in the Korats, and breeders should bear this fact in mind.

Referring to breeds which were based on genetic mutations, he mentioned the Scottish Fold, which was not registered in the GCCF although the Manx cat was; however recognition of the Manx had taken place a long time ago. There were new breeds coming along such as the Japanese Bobtail, which is a breed based on a defect. If one of the accepted breeds had such a tail, it would be considered a defect so he questioned the wisdom of accepting a breed that was based on a defect. Whilst individuals may not have an interest in these breeds, the public perception would be that these defective breeds were accepted in the cat fancy.

He finished on a cheering note with the announcement that FIP research at Utrecht University appears to have identified a specific mutation associated with FIP. Whilst this did not address the problem of prevention, this could lead to a reliable diagnostic test, which would be a big step forward.

Professor Leslie Lyons.

The next speaker was the well-known geneticist, Professor Leslie Lyons who spoke on “Genetic Tests to Maximise Healthy Breeding and the Quality Health of Cats” Professor Lyons, like Professor Gruffyd-Jones is also well known personally to many of the delegates as well as the cat fancy in general and her talks are always welcomed.

Professor Lyona is a charismatic speaker who illustrates her lecture with many slides and it is not easy to report verbally on the subjects she touched upon.

She commenced by speaking of what she described as the “slippery” slope of ethics, by which she meant where to place certain conditions or breeds on a hypothetical slope, as different people would have different views. She showed a slide illustrating the genetic point of view where taillessness and PKD are severe mutations, so severe that with two copies of them they are lethal in utero so from a genetic point of view they are bad. However PKD could survive through the cat if there was only one copy and some cats do not get kidney disease at all, which showed it to be a tricky mutation. Where to put other conditions on the “slippery slope” was a problem. Where, for example, should Scottish Folds, Brachecephaly or Polydactyly be put? She did not have a problem with polydacyly, she did not accept that it was better for these cats to walk on the snow as Siberian Tigers, Lynx and Snow Leopards did not have extra toes, so there was no truth in that assertion.

Her criteria as a geneticist were what would happen if they were all turned loose in the wild. Anything that had to be done for a cat, such as wiping its eyes or helping it to deliver kittens was not natural and should not be necessary so all those things should be taken into account. All that was required of a cat was the ability to procure energy by utilizing its food properly and to be able to produce offspring. Mutations affect reproduction. Mutations leading to death in utero were obviously not good. Some mutations affected a cat prior to its breeding life but others didn’t appear until later in life, at which point it was too late to do anything about it. It was not easy to decide which mutations should be eliminated. Her philosophy was that the “needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few.” She thought that the work, which was being done in her lab, was preventing more sick cats than most veterinarians could do in a lifetime. They could prevent hypokalaemia and polycystic kidney disease and this was saving thousands of cats. She pointed out that once the knowledge was there, it brought with it the ethical responsibility of using it properly.

In-breeding could be established by using co-efficients if the pedigree was correct, but she thought it was probable that the pedigrees were not always correct because of accidents etc. thus the in-breeding co-efficient was not necessarily correct. The other way to arrive at genetic diversity was to use the genetic markers that they had been using for some years in her lab. From the Korat study, it had been shown that their estimates to a large extent matched the pedigrees, which was very positive. She referred to the fact that one of the members had said they were a genetic registry and she challenged that, as unless the parent cats had been parentage tested, it was impossible to make this statement.

Referring to their cat studies, she explained that the cats from the East were most related to the feral cats of the East and the cats of the West were most related to the feral cats of the West. They were continuing with this study. She illustrated these findings on a chart. She then spoke of the world populations of cats, European cats, cats from Egypt. Cats from Iraq and Iran, the Arabian Sea cats were slightly different genetically, cats from Kenya, which were probably brought in by the British and so they actually represented European cats. She explained that when we speak of outcrosses, we have populations of origin to go to and help diversify the cat breeds.

At this point in time Professor Lyons could not genetically distinguish the difference between a British Shorthair and an Exotic Shorthair. Scottish Folds were also similar but could be genetically defined. The Selkirk Rex mutation could be genetically defined but a straight coated Selkirk or a straight eared Fold both looked like British Shorthairs.

The first genetic study they had done was on the Havana Browns. They had then expanded to look at Turkish Vans and Turkish Angoras, which proved to be genetically the same. They had also received samples from cats which looked like Turkish Vans and in some cases they proved to be genetically Turkish Vans but in others not. Eventually they extended the study still further and established that the breed that most matched the street cats of Turkey was the Turkish Angora. The Van is also a Mediterranean Turkish cat which had apparently been separated long enough from the others to become a separate breed genetically. There were also cats that had been looked at from Cyprus and they were genetically different to the other breeds of the region.

John Hanson had raised the point, a year previously, that cats on an island would perhaps be genetically different from those on the mainland. Professor Lyons had looked at the cats on Hawaii but found it was not true for them, neither was it true for one of the Carolinian Islands off the coast of California or for cats from Majorca which proved to be the same as cats from Spain and Portugal so it would seem that the Cyprus cats could be a unique group.

Following on with the genetic makeup on the cats from Spain and Portugal, it would appear that in common with other flora and fauna in the province of Iberia, their genetic makeup was unique.

They had been asked to look at European cats and found that most of the samples submitted were most similar to the feral cats of Finland rather than other countries of Europe, for example Germany.

She then showed a slide illustrating the different breeds and their genetic diversity and spoke of the Burmese. One of her recommendations was that the Burmese all over the world should work together, irrespective of whether they were from Europe or Australia or were traditional or contemporary American Burmese. She recommended that they be mixed up in the interests of saving the breed from extinction. Also some of the Asian cats could be used as they could be genetically tested.

Another recommendation was that, as her data was getting rather old, she would like to update it and now that the genetic ancestry test was available, the breeders should take samples of their breeding cats and send them in as a group. This way the genetic diversity could be established. It was also necessary to know how big the population was and how many breeders were involved.

The world has changed in the last two years because of the development of a DNA chip. 12 cats could be put on one chip and 63,000 markers could be tested at one time. This has helped tremendously to identify new genetic mutations etc. Her aim was to find out every possible genetic mutation. Mutations, she maintained, were good. There were about 3 GB of DNA making up about 25,000 genes on about 38 different chromosomes which were arranged differently in different species; out of these 25,000 genes what differentiated a cat were only a few hundred unique genes, it was a matter of when these genes turned on and turned off. To illustrate this and on a humorous note, she said there was a gene which made whiskers and put spines on the penis, fortunately in humans the promoter for that gene was turned off. About two thirds of the mutations that needed to be found were in the promoter part. These more difficult areas needed to be looked at, including the inhibitors and here she referred to silver, the mutation for which to date they had not been able to find but they were still working on it. Mutations occur all the time, every egg and sperm has about 30 different mutations, however none of this was apparent until there was offspring from that egg and sperm. Mutations gave variation in coat colour, they could adapt the individual to environments, and they generated new sub-species and species, making an animal good for a particular environment, therefore they could be good. They could also be bad, causing poor health and disease susceptibility so the good and the bad had to be balanced.

The tabby mutation had recently appeared, there were 3 or 4 mutations that caused a cat to have classic tabby, and a locus had been re-named as ‘ticked.’ That is the second part of the tabby locus, which says pattern on or pattern off, if the cat has two copies and ‘pattern on’, it will be a classic tabby – it is recessive. She estimated that white spotting would be a lifetime experience. Under Agouti there was a different allele representing Asian Leopard Cat for charcoal. It gives a different colouration that is hard to identify. They selected for one allele that came from the ALC and if there was one domestic cat non-agouti allele and one ALC, allele it produced the charcoal Bengal.

Professor Gruffyd-Jones would like samples of Caramel on which she could work. Such samples would also have to be shared with other investigators. Regarding Amber, there was no reason why this could not be tested for in any other breed. She commented that some coat colours caused health problems, for example Siamese Strabismus which was due to incorrect wiring in the brain. The same gene for dilution causes alopecia in dogs but not in cats. They do not yet know the location of the gene controlling pattern on and pattern off.

Dominant white deafness would be really hard. It was an old mutation which was in the cat population before all the breeds developed. This could be the reason why some are deaf and some are not or it could be random vibration of the melanocytes, which were involved in the colouration of the ears and eyes; it could be random or genetic but it would take some time to find the answer.

The Cornish Rex woolly hair syndrome could, in humans, lead to dental problems, alopecia and similar conditions; so the same genes having different mutations in another species can cause a severe health defect.

Mutations for Sphynx and for Devon had been found and, as predicted by Roy Robinson, these concerned a different mutation of the same gene, this is true also for the Selkirk Rex. So there were three mutations of the same gene. In Longhair there are four different mutations of the same gene. They also have a good location for La Perm and for the Peterbald and possibly for the Tennessee Rex, which was another curly coated breed in the US that had not been developed.

Morphological traits present some problems. There was a test for polydactyly, there were two mutations and they did not correlate with the number of toes which would be present. She suggested that where the mutations existed butwithout extra toes, there were no health problems. She acknowledged that there were issues with extra toes. The Scottish Fold mutation had been found and it was now possible to test as to whether a cat had one or two copies. She suggested that only cats with one copy should be registered and that those cats should have a radiograph when the cat was ready to breed to see if it was developing osteoarthritis. If there was something positive on a radiograph, the cat concerned might not be a good cat to breed with. Maybe it would also be a good idea to radiograph the same cat later in life to see how it progressed. This could also be an interesting study from the health point of view for humans.

Taillessness was also identified. There were actually several different mutations of the same gene which did not correlate. If there was one copy, it might be a rumpy, a stumpy or a rumpy riser. She recommended that, to be safe, a rumpy should only be mated with a long tailed cat.

The Pixiebob had the same tailless mutation as the Manx, as well as the Japanese Bobtail. Japanese Bobtails were also missing a thoracic vertebrae otherwise there were no health issues and the lack of a thoracic vertebrae evidently created no problems. She had no issues with the Japanese Bobtail. They were still working on the American Curl in collaboration with the University of Sydney.

They were working with Iowa State on Brachycephaly They expect to find the genes involved with the development of Brachycephaly outside of Burmese cats. The Burmese head defect is a major gene that causes Brachycephaly.

Munchkin has yet to be looked at.

With regard to the Peterbald, she had been asked if these cats showed an immune deficiency in the homozygote form – she was not yet sure. Neither was she sure about the cause of the different coat types.

The other thing that was important was to know the frequency of the mutation in a population before it was possible to decide to get rid of it or how o manage it. To do that unbiased data was needed. If a group of cats had been tested for PKD and then needed to know whether they had another condition, the unbiased set of samples was already available. If the frequency was low, she recommended removing it from the population, if it were high then it had to be managed. The easiest one to get rid of is a dominant gene with low frequency in a big population. With regard to those with low frequency and a recessive gene, she questioned why Glycogen Storage Disease in the Norwegian Forest Cat and Spinal Muscular Atrophy in the Maine Coon had not been eliminated. There were large diverse populations of cat and it should be possible to get rid of these conditions. Was it necessary to be very careful with Burmese with Hypoleukaemia and Head Defect and now there was the mutation for oral facial pain as well – the answer was a definite yes. Overall testing gave the possibility to make good decisions and it could be used as a marketing tool, which would give peer pressure. However genetic testing did not give the severity of a condition and the veterinary surgeon was still needed to learn how to manage the problem.

Mentioning on-going research projects, hydrocephalus in cats had come up. Samples were needed. The Burmese, being so inbred, had been a goldmine of information. However, the more outbred the cats were, the more samples were needed. There were other conditions to be looked at such as hip dysplasia in Ragdolls. She said also that they could never have enough samples of FIP.

The last point she made was that she intended to make it possible, in her lifetime, to sequence a sick cat. To be able to do that it was necessary to define all the genetic variations that were already there, so that when something new appeared, it could be identified. The database had to be large enough to contain all the normal genetic data and then pick up the new thing that might mean something. She was calling it the 99 lives cat gene project. She pointed out that the horse and dog world were well ahead and the cat world needed to step up. She urged people to think of a way of making it possible. It would be an expensive project but well worthwhile.

Professor Lyons is leaving UC Davis and moving to Missouri but the co-operation with UC Davis will continue and she will be a Professor emeritus, remaining on the faculty.

Asked about Lymphosarcoma in cats, Professor Lyons said she would welcome samples, as this was one of the subjects she was very interested in.

One of the questions asked of Professor Lyons was what information she had on Manx breeding on the Isle of Man. She responded by saying that she had visited the Isle of Man on two occasions to collect samples. There were a couple of different mutations in the cats on the island. There is a Manx sanctuary there but she explained that the person at that sanctuary would really like the Manx mutation to go away because she sees the unhealthy specimens. Of course the unhealthy ones were not running about on the island as they were either so unhealthy they died or had to be put down. She would absolutely say that breeding rumpy to rumpy was very unhealthy.

Asked if it would be useful to get cats swabbed, for example, at shows, she replied that she was very much in favour of swabbing as many cats as possible. It was remarked that this had been tried at a UK show but not all breeders were willing to have their cats swabs Professor Lyons had, however, had great success at a show in Turku in Finland when nearly all the cats in the show were swabbed. She thought the time had come to try and establish a true genetic registry. It would be good to pick a population and start a genetic registry with that group. She congratulated the breeders who had used the test for hypokalaemia and commented that the American Burmese breeders were, sadly, not using the test for the head defect, indeed half the testing was coming from Europe. This showed that European breeders and also Australian breeders had the head defect. She strongly recommended outcrossing although she knew this was controversial and pointed out that it was now possible to swab for a DNA test and also to get a DNA fingerprint.

The last item on the Agenda was the Open Session in which people are encouraged to put questions to the WCC delegates. This part was reported in the Minutes.

It was generally agreed that the whole weekend had run smoothly and successfully and the delegates spent a quiet evening in preparation for the Business Meeting of the WCC which took place on the Monday, the Minutes of which will appear shortly on this site.

The Minutes of the meeting are available for download.